Forest Ecosystem Restoration: Strategies for Degraded Landscapes

Table of Contents

I. The Need for Forest Ecosystem Restoration

Forest ecosystems are declining because of problems like deforestation, climate change, and urban growth, making it urgent to restore these areas to fix their ecological health. These ecosystems are important not just for biodiversity; they also play key roles in carbon capture, water cleaning, and providing resources for nearby communities. To address the balance of being vulnerable and resilient, good restoration plans need to involve community-based methods that use local knowledge with scientific methods to guarantee long-term success. For example, [citeX] shows the clear difference between vulnerable and strong forest communities, highlighting the need for flexible strategies that help local people while restoring essential ecosystems. This broad view deals with immediate environmental issues and connects with bigger topics of social fairness and environmental justice in forest management, showing the need for a complex approach to repairing ecosystems.

A. Effects of Forest Degradation on Biodiversity and Climate

Forest damage brings big risks to biodiversity and climate stability, disrupting important ecological balances needed for life. Losing forests causes habitat splitting, leading to drops in species numbers and a loss of genetic variety. This biodiversity issue worsens with climate change, as changing weather affects where species live and how they survive. Furthermore, when forests are cut down, they let out lots of stored carbon dioxide, which adds to global warming (Bodegom et al.). Good restoration methods should focus on fixing damaged landscapes while using tactics that strengthen both ecosystems and local communities. The image showing High vulnerability to climate change against High resilience to climate change clearly shows the challenge many forest ecosystems face now, highlighting the need for sustainable management practices that support both biodiversity and climate change efforts.

B. Case Studies of Severely Degraded Forests

Studying cases of badly damaged forests gives important information about the environmental and social effects of cutting down trees. For example, in Latin America and the Caribbean, more than 300 million hectares of forests are said to be damaged, which causes serious problems for ecosystem services and increases hunger among local people (Ana R Rios et al.). This worrying situation connects to a larger problem of global land damage that threatens the lives of about 1.5 billion people around the world. This is very clear in dry areas, where yearly damage affects around 12 million hectares of land each year (Monge M et al.). The consequences of this damage can be serious, including less biodiversity, more greenhouse gas emissions, and lower agricultural output. Therefore, effective restoration efforts need to focus on getting the community involved and using traditional ecological knowledge, which has been proven to be important in not just making these landscapes stronger but also in improving the social structures of the communities that rely on them for survival. An image that highlights the need for community involvement in protecting the environment shows the teamwork needed for successful restoration efforts, showcasing real-world examples of good cooperation. By engaging local people and groups in the restoration work, we can build a sense of ownership and responsibility. Additionally, by looking at the main causes of degradation, such as logging, farming expansion, and climate change, we can develop specific strategies that help both ecological recovery and community well-being, ultimately leading to a more sustainable future for the environment and its people.

| Location | Year | Degradation Type | Area Restored (hectares) | Restoration Strategy | Success Rate (%) |

| Brazil – Atlantic Forest | 2021 | Deforestation and Agriculture | 15000 | Native Species Planting | 75 |

| Indonesia – Sumatra | 2022 | Logging and Oil Palm Plantations | 8000 | Agroforestry | 65 |

| United States – Appalachian Region | 2020 | Coal Mining | 5000 | Reforestation with Local Species | 80 |

| Australia – Karri Forests | 2023 | Wildfire and Logging | 12000 | Controlled Burns and Planting | 70 |

| Ethiopia – Bale Mountains | 2021 | Overgrazing | 3000 | Community Managed Forest Restoration | 85 |

Case Studies of Severely Degraded Forests

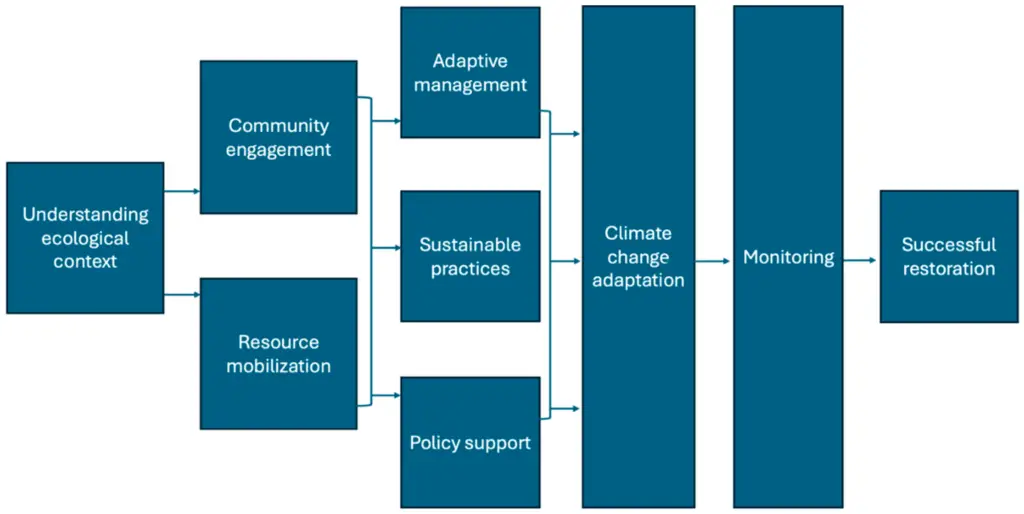

II. Key Strategies for Restoration

Good forest restoration plans need to use different methods that involve local people, focus on biodiversity, and include flexible management techniques. Acknowledging how ecological health and human wellbeing are linked, approaches like Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) support both passive and active restoration techniques to improve ecosystem benefits and community livelihoods at the same time (del Castillo et al.). In Latin America, for example, degraded areas lead to major forest cover loss, which increases greenhouse gas emissions and harms the environment (Ana R Rios et al.). By focusing on involving stakeholders and building community skills, initiatives led by locals can use traditional knowledge to strengthen resilience to climate change, driving the restoration toward lasting results.

IMAGE – Conceptual framework for climate change adaptation and restoration (The image provides a conceptual framework for climate change adaptation and successful restoration. It illustrates various interrelated components, including ‘Understanding ecological context,’ ‘Community engagement,’ ‘Resource mobilization,’ ‘Adaptive management,’ ‘Sustainable practices,’ and ‘Policy support.’ These elements collectively contribute to ‘Climate change adaptation,’ which is further linked to ‘Monitoring’ and culminates in ‘Successful restoration.’ The diagram indicates a systematic approach to managing ecological challenges rooted in effective community collaboration and policy implementation.)

A. Reforestation and Tree Planting Techniques

In the field of reforestation and tree planting methods, using native species has become a key approach for improving ecological strength and boosting biodiversity. Using local types of trees helps them adjust to changing climates, supports soil wellness, and helps restore ecosystem benefits that are essential for human populations and the health of our planet. For example, studies show that choosing the right genetic types for specific locations can greatly improve restoration work by increasing the survival and growth of new trees, which also benefits nearby plants and animals. Moreover, methods like passive restoration within teamwork can produce lasting results while meeting local economic needs, thus making the restoration process more effective and encouraging community input in land use decisions (Bordacs et al.), (del Castillo et al.). The connected advantages of these methods point to a pressing need for community involvement and supportive policies. This is especially important in urban areas that show how essential forests are for community well-being. Urban reforestation can help improve air quality, lower heat effects, and boost property values, making it a complex approach to city planning. All these methods are key in tackling the issues posed by damaged lands. They remind us that reforestation isn’t just about planting trees but also about restoring ecosystems, helping local wildlife, and improving human lives sustainably. Stressing the role of education and awareness in these initiatives further emphasizes the urgent need for joint action and coordinated strategies that resonate across different communities and ecological areas.

B. Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR)

Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR) is an important way to deal with problems in forest ecosystems, offering a cheaper option compared to regular reforestation. This method uses the natural ability of ecosystems to heal by promoting the growth of existing plants while tackling outside problems like illegal logging and environmental harm. These issues are examined in the study of Pterocarpus erinaceus in The Gambia (Sanneh et al.). By using ANR, areas that are damaged or have been cleared can be restored properly, which helps to improve biodiversity and strengthen resilience against climate change effects. This restoration approach not only benefits the local ecosystem but also aids in keeping genetic diversity, creating a better environment for many plant and animal species. Additionally, this method highlights the need to think about genetic factors in restoration efforts, indicating that choosing native species carefully is essential for lasting success and ecological balance (Bordacs et al.). By using ANR, communities can promote both environmental health and economic stability, showing a proactive method to managing forests that aligns with broader ecosystem restoration goals. This connection is crucial, as it ensures that a region’s ecological needs are satisfied while also helping local people’s livelihoods. The complexities of these relationships can be better understood through detailed case studies and success stories, highlighting the integrated strategy required for effective watershed management and the revival of natural resources. In the end, ANR shows how effective it can be to work with nature’s ability to recover alongside local communities.

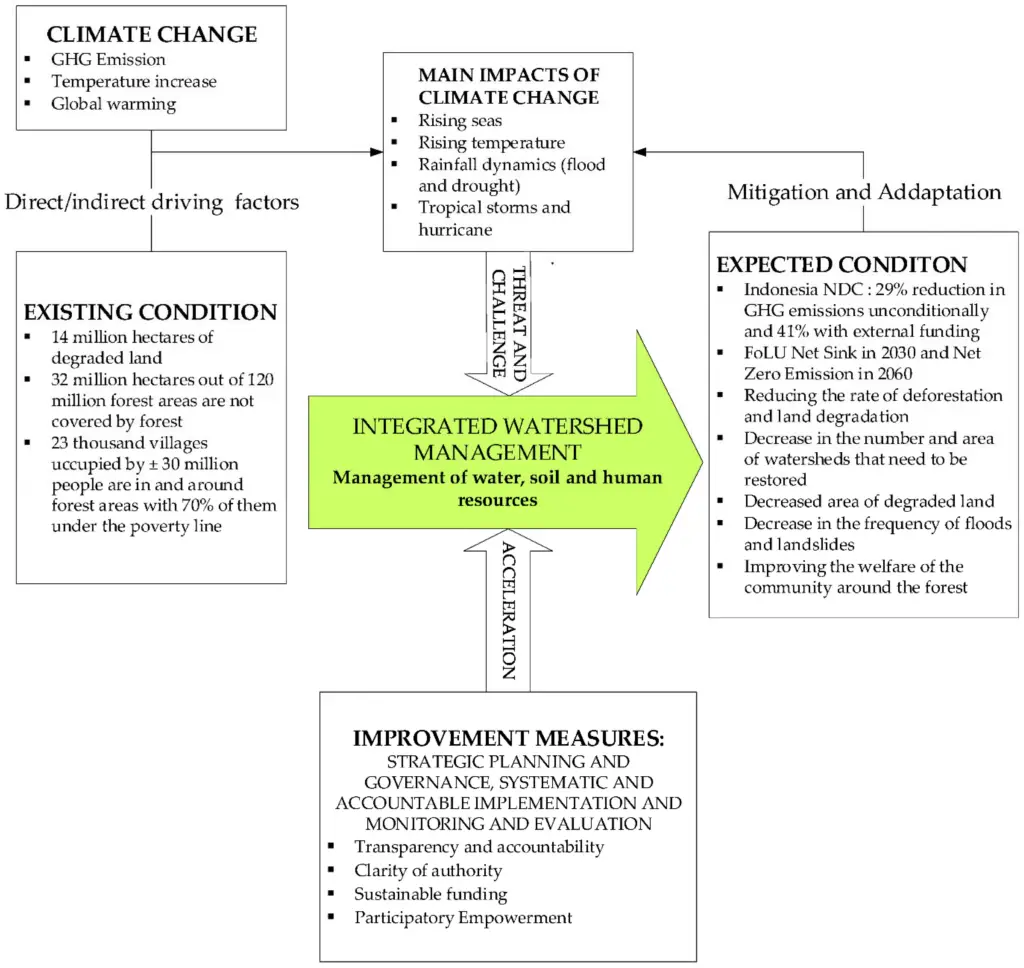

III. Challenges in Forest Restoration

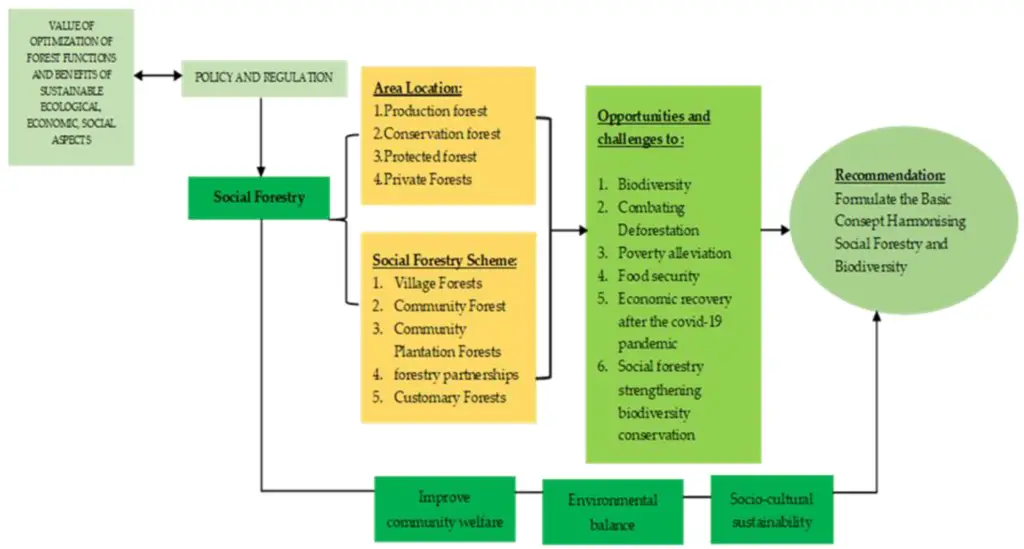

The challenges in restoring forests are complex and require an approach that considers ecological, social, and economic factors. One significant obstacle is getting local communities involved, which is often difficult due to a lack of understanding about the benefits and goals of restoration. Local people may not see how healthy forests can benefit their livelihoods, leading to indifference or opposition to restoration efforts. Research shows that successful Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) projects need to involve multiple stakeholders, but gaining their participation is challenging because of different interests and scarce resources ((del Castillo et al.)). Community members often have varying priorities that can clash with restoration aims, making it essential for planners to handle these differences carefully. Furthermore, limitations in policy and institutional support can hinder restoration activities, making coordination for effective action more difficult ((Program CR on Forests et al.)). For example, community-led initiatives often face challenges without strong governance and suitable regulations, emphasizing the need to empower local organizations to push for sustainable practices. Without systems to encourage community participation, engagement often fails, resulting in practices that contradict restoration goals. This complicated issue highlights the need for well-rounded strategies, as seen in [extractedKnowledge1], where social forestry is examined for its potential to improve community well-being and environmental strength. Formulating these strategies involves not just teaching local communities about the benefits of forests but also developing incentive systems that match both individual and collective interests, promoting a collaborative approach to restoration.

A. Balancing Human Needs and Conservation Goals

Getting balance between what people need and conservation goals requires a simple approach that recognizes how ecosystems support both environmental health and community living. This complexity shows the need to think about different factors, such as economic, social, and environmental aspects, in discussions about conservation. Nature-based solutions are important here, as they encourage practices that are not only good for the environment but also make sense economically for local people, leading to better living conditions for both humans and nature (Cecchi et al.). Approaches like community forestry and sustainable farming can build resilience against climate change and provide benefits for local communities through better resource management and economic opportunities. By using methods that fit ecological practices with local customs and knowledge, we can create a feeling of ownership among community members. Moreover, the success of these projects often depends on active participation from the community, as shown in examples where local knowledge leads to better restoration goals and a clearer understanding of ecosystem behaviors. This participatory method supports the idea that conservation can’t work alone; it must be connected with the lives of people who rely on these ecosystems for their everyday needs. By focusing conservation efforts on human well-being, it becomes possible to create a way forward that supports ecological health while addressing urgent socio-economic challenges faced by marginalized communities, thus encouraging long-lasting sustainability and social fairness (Bradbury et al.). In this way, a relationship that benefits both nature and people can be developed, ensuring that both thrive together.

B. Addressing Climate Change Impacts on Restoration

Dealing with the effects of climate change on restoring forest ecosystems is very important for making damaged landscapes more resilient and helping these areas cope with ongoing environmental changes. As climate change becomes worse, restoring ecosystems requires a complex approach. This should involve local communities, the use of indigenous knowledge, and the use of adaptive management strategies that fit specific ecosystems. By recognizing the link between ecological health and social-economic factors, restoration efforts can align with broader sustainability goals, allowing both nature and human communities to prosper. Effective restoration depends on a clear understanding of a region’s weaknesses, as shown by the problems that tropical forests face due to serious deforestation and habitat loss from human actions and natural causes. Additionally, policies based on solid scientific research can help set up frameworks that encourage community involvement and facilitate the ongoing monitoring of ecological results over time (Program CR on Forests et al.)(Program CR on Forests et al.). In the end, including these diverse views in restoration projects leads to stronger and more adaptable responses to the unique problems brought on by climate change. This ensures restoration activities not only tackle immediate environmental concerns but also offer important long-term ecological and social benefits for future generations. This all-encompassing strategy highlights the need for teamwork among scientists, policymakers, and local communities in the commitment to secure a sustainable future amidst climate uncertainty.

IV. Community Involvement in Restoration

Community involvement is very important in restoring forest ecosystems, as it helps local people take care of their environment and boosts ecological strength. Good community engagement not only shows how local communities rely on forest resources, like fuelwood, but also makes use of their traditional knowledge to guide restoration efforts ((del Castillo et al.)). Additionally, empowering and building skills in local communities is key in allowing them to be part of decision-making, creating a feeling of ownership over restoration activities ((Program CR on Forests et al.)). Visual tools, like images, clearly show how community involvement makes a difference, highlighting joint actions in environmental cleanup projects. These pictures remind us of the real results that can come from working together on restoration projects. By bringing in local views and resources, restoration plans can meet both ecological and social goals, ultimately aiding sustainable development in damaged areas.

A. Role of local communities in restoration efforts

Local communities are key to making forest ecosystem restoration work well because they offer useful knowledge, care, and resources, which help these efforts succeed. Their strong ties to the land create a sense of ownership that is important for managing resources sustainably, making them critical partners in the restoration efforts. The research on Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) shows that involving local stakeholders effectively can help find tree species that have economic value and are suitable for the local area, enhancing ecosystem services such as more biodiversity, better soil quality, and improved water conservation (del Castillo et al.). Yet, there are still challenges, such as socioeconomic gaps, limited access to information, and the need to build skills and knowledge in these communities. Empowering local individuals through education and teamwork has been proven to boost their participation and, in turn, the success of restoration plans. Involving these communities in decision-making allows for their unique views and needs to be considered, leading to more effective and customized restoration efforts (Program CR on Forests et al.). Illustrations of community-led restoration, shown in recent studies and projects, highlight the possibilities of engaging local actions for ecological recovery and sustainability, while also demonstrating the wider impact of community restoration efforts. This cooperation not only supports environmental wellbeing but also strengthens community ties and encourages a shared responsibility for caring for their natural resources.

B. Education and awareness programs for sustainable practices

Programs for education and awareness are very important for supporting sustainable actions needed to restore forest ecosystems. By helping local communities understand the true value of biodiversity and the need for managing resources sustainably, these programs encourage community participation in restoration work. For example, programs that mix indigenous knowledge, local traditions, and community involvement, like the one shown in the image of community environmental efforts, demonstrate how educational strategies and practical actions work well together. They show that local knowledge can effectively guide and empower restoration efforts. Also, raising awareness about climate change and the many benefits trees provide can inspire local communities to take more active steps in restoration, which is highlighted in the discussion of spreading ecological knowledge (del Castillo et al.). Such educational initiatives aim to create a deeper appreciation for the environmental benefits forests offer, which are supported by policies that stress the importance of conservation. Education and policy together highlight the need to improve community resilience against environmental changes and tackle issues caused by climate change. This combined approach not only leads to better decision-making but also strengthens long-term sustainability goals by making sure communities have the knowledge and resources to practice effective conservation methods (Bodegom et al.). In the end, the successful combination of education, local participation, and supportive policies is key to nurturing a culture of sustainability that can endure amidst environmental challenges.

| Program Name | Year Established | Participants (Annual) | Focus Area |

| National Environmental Education Foundation (NEEF) | 1990 | 500000 | Public engagement and education |

| Project Learning Tree (PLT) | 1976 | 80000 | Environmental education for teachers and students |

| Eco Schools USA | 2006 | 150000 | Sustainable practices in schools |

| Forest Stewardship Program (FSP) | 1990 | 120000 | Sustainable forestry practices |

| Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) | 1994 | 400000 | Forest management and sustainability |

Education and Awareness Programs for Sustainable Practices

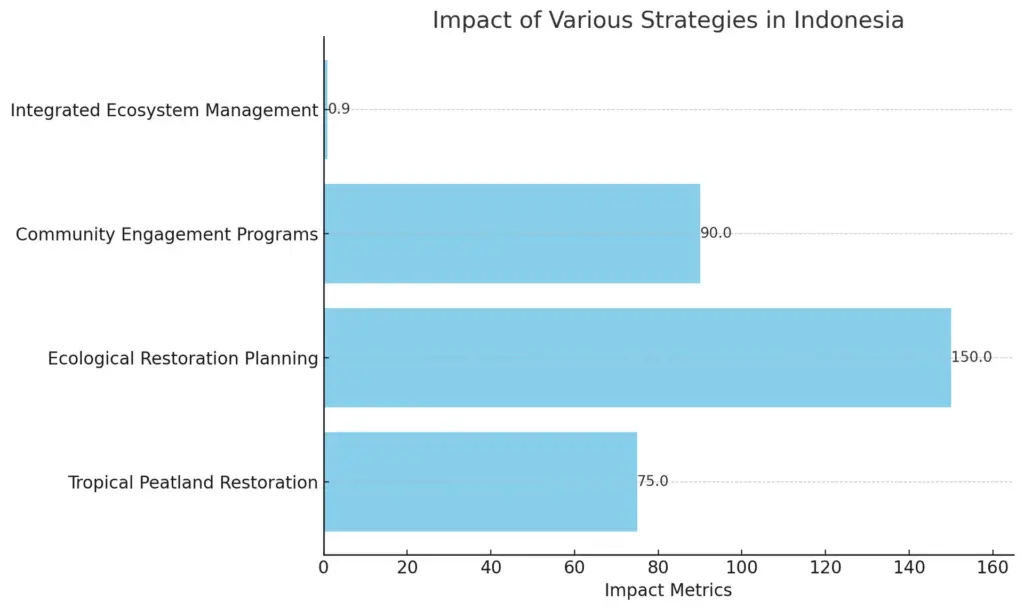

V. Success Stories in Forest Restoration

The successes in restoring forests, especially in tropical areas like Indonesia, show a range of methods that can help fight ecosystem damage. Effective projects have shown they can not only bring back native plants but also increase biodiversity and capture carbon. For example, different restoration efforts have reached agreement on the need for ecological restoration, while opinions on how effective it is and how it looks vary, as shown in the analysis of Indonesia’s tropical peatland restoration efforts (Agus et al.). Additionally, the combined approach to ecological restoration highlights the need for scientific methods along with social and economic factors, making it a well-rounded answer to sustainability issues (Yohannes H et al.). These success stories illustrate a complex understanding of restoration that can guide best practices and motivate future work in damaged areas around the globe.

The chart displays the impact of various strategies implemented in Indonesia for environmental sustainability. Each bar represents the effectiveness of a specific strategy based on different impact metrics, illustrating the outcomes achieved in enhancing biodiversity, ecosystem health, and community engagement.

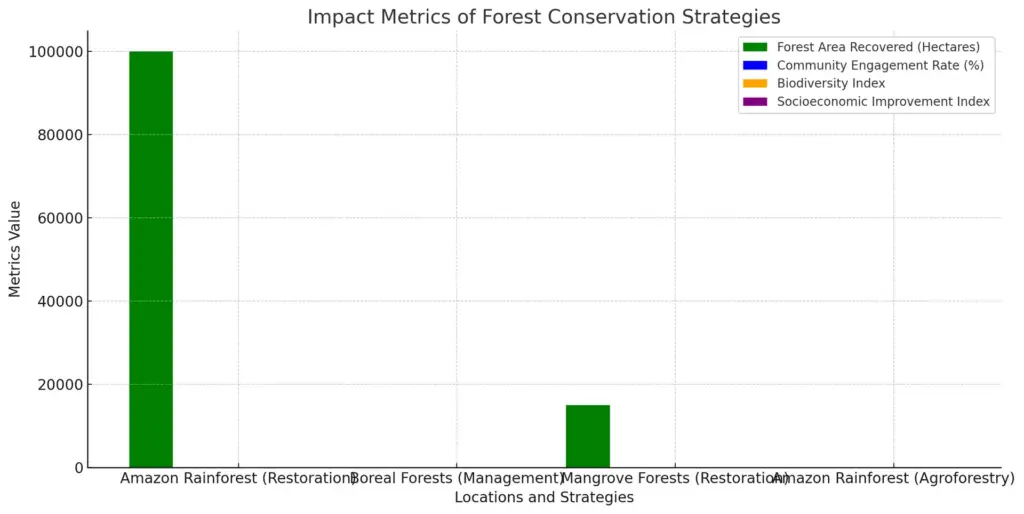

A. Examples from Amazon, Boreal, and Mangrove Forests

When looking at restoration strategies used in different ecosystems, examples from the Amazon, Boreal, and Mangrove forests show both specific challenges and common principles for forest ecosystem restoration that should be viewed together. The Amazon rainforest, known for being one of the most biodiverse areas on Earth, faces significant deforestation mainly because of agricultural and logging activities. This situation calls for strategies that focus on ecological health while also considering the socioeconomic factors that help gain community support and involvement in the restoration efforts. On the other hand, Boreal forests are mainly degraded due to climate change and industrial activities like mining and oil extraction, so restoration strategies here must change to cope with new environmental challenges, such as changed rainfall and temperature patterns. Mangrove forests stand out because they act as vital coastal barriers against storm impacts and erosion, and they also support many aquatic species. This highlights the need for restoration methods that consider tidal effects and salinity changes while dealing with development and pollution issues. Linking the lessons from these different ecosystems is essential, as creating a standard way to evaluate restoration success—similar to the use of ecological guidelines—could improve the results of these efforts in many situations. This is reflected in the increasing advocacy for policies that emphasize ecological health and acknowledge primary forests as vital resources that need protection for future generations (Adams et al.), (DellaSala et al.). In conclusion, recognizing the unique needs of each forest type and applying common restoration principles will help create more resilient and successful ecosystems around the globe.

The chart displays the impact metrics of various forest conservation strategies across different locations. It includes metrics for forest area recovered in hectares, community engagement rates as a percentage, biodiversity indices, and socioeconomic improvement indices. The Amazon Rainforest shows a significant recovery area along with high community engagement, while the other locations reflect different aspects of conservation efforts, highlighting the effectiveness of each strategy.

B. Community-Based Forest Restoration Programs

Community-Based Forest Restoration Programs are key in fixing damaged lands with help from local people. These programs use traditional knowledge and practices, creating a sense of ownership that is important for keeping restoration efforts going. They not only work to bring back ecological balance but also help improve local economies by offering financial benefits through the sustainable use and care of forests. Involving communities in these efforts often results in better biodiversity, as shown in many cases where successful results happened in different areas. Additionally, these programs help build social ties, encouraging teamwork among community members, which is crucial for long-lasting success. A good example of how community engagement links to environmental restoration is seen in [citeX], which discusses the problems caused by climate change and the strategies local people use to adapt, ultimately showing the benefits of community-focused methods in restoring forest ecosystems.

| Program Name | Location | Year Started | Area Restored (acres) | Community Involvement | Funding Sources |

| Restore America’s Estuaries | United States | 2000 | 50000 | Local volunteers, schools, NGOs | Federal grants, private donations |

| Woods and Water | Michigan, USA | 2011 | 15000 | Local residents, businesses | State funding, partnerships with corporations |

| Trees for the Future | Worldwide (focus in Africa and Asia) | 1989 | 200000 | Farmers, local organizations | International grants, donations |

| East Africa Forest Restoration Initiative | East Africa | 2015 | 30000 | Local communities, schools | Global environmental funds, NGOs |

| Reforestation with the Community | California, USA | 2016 | 25000 | Community groups, students | State and federal grants, community fundraising |

Community-Based Forest Restoration Programs

REFERENCES

- del Castillo, R.F, Echeverría, C., Geneletti, D., González-Espinosa, et al.. “Forest landscape restoration in the drylands of Latin America”. ‘Resilience Alliance, Inc.’, 2012, https://core.ac.uk/download/19792927.pdf

- CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. “CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry – Plan of Work and Budget 2020”. CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry, 2020, https://core.ac.uk/download/288633648.pdf

- Ana R. Rios, Luciana Gallardo lomeli, Paul Isbell, Ronnie De Camino, Steven Prager, Walter Vergara. “The Economic Case for Landscape Restoration in Latin America”. World Resources Institute (WRI), 2016, https://core.ac.uk/download/75760917.pdf

- Monge Monge, Adrian Antonio, Tigabu, Mulualem, Yirdaw, Eshetu. “Rehabilitation of degraded dryland ecosystems – review”. 2017, https://core.ac.uk/download/84363331.pdf

- CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. “CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry – Plan of Work and Budget 2020”. 2020, https://core.ac.uk/download/288633648.pdf

- Sanneh, Omar. “Assessing natural regeneration of Pterocarpus erinaceus in Kiang West National Park, The Gambia”. Universidad Internacional de Andalucia, 2023, https://core.ac.uk/download/588381669.pdf

- Bordacs, S., Boshier, D., Bozzano, M., Cavers, et al.. “Genetic considerations in ecosystem restoration using native tree species. State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources – Thematic Study.”. ‘Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)’, 2015,

- Bodegom, A.J., van, Savenije, H., Wit, M., et al.. “Forests and climate change: adaptation and mitigation”. Tropenbos International, 2025, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/29250443.pdf

- Lu, Y., Mcdonagh, J., Stocking, M.. “Global impacts of land degradation”. Overseas Development Group (ODG), Norwich, 2006, https://core.ac.uk/download/2779887.pdf

- Cecchi, Claudio, Egbert, Roozen, Eva, Mayerhofer, Jurgen, et al.. “Towards an\u2028 EU research and innovation policy agenda for nature-based solutions & re-naturing cities. Final report of the Horizon 2020 expert group on nature-based solutions and re-naturing cities.”. Publication office of the European Union. Directorate-Generale for Research and innovation. European Commission., 2015, https://core.ac.uk/download/54517673.pdf

- Bradbury, Richard, Broadmeadow, Mark, Brown, Kathryn, Crosher, et al.. “Biodiversity 2020: climate change evaluation report”. Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), UK Government, 2020, https://core.ac.uk/download/288346146.pdf

- Agus, Fahmuddin, Hamer, Keith, Hariyadi, Bambang, Hill, et al.. “Wading through the swamp: what does tropical peatland restoration mean to national-level stakeholders in Indonesia?”. ‘Wiley’, 2020, https://core.ac.uk/download/395371876.pdf

- Hamere Yohannes, Hamere Yohannes. “Integrated Ecological Approach as Paradigm Shift towards Sustainability: Current Efforts and Challenges”. Global Journals Inc. (US), 2018, https://core.ac.uk/download/581121339.pdf

- Adams, Josh. “Evaluating the Success of Forest Restoration”. PDXScholar, 2015, https://core.ac.uk/download/37773640.pdf

- DellaSala, Dominick A., Foley, Sean, Hugh, Sonia, Kormos, et al.. “Policy options for the world’s primary forests in multilateral environmental agreements”. ‘Wiley’, 2014, https://core.ac.uk/download/43366956.pdf